Elon Musk doesn't play by the rules. The rules matter.

Elon needs to grow up.

Today's post has a large attachment. Matt Levine broadcasts an e-mail called "Money Stuff." It is an opinion piece from Bloomberg, sent to me free. I am including their advertisement, because that is how they get paid. If readers find it interesting--I certainly do--then subscribe to Levine's emails, subscribe to Bloomberg, maybe shop at Polo. Levine and Bloomberg broadcast this information hoping it draws people in. I want to encourage high quality content like this.

He is an extraordinarily successful entrepreneur. He left Stanford to create a software company that got bought by Compaq for $307 million dollars in 1999. He then co-founded a bank that got merged and ended up part of PayPal, providing another huge payday. He then founded SpaceX and Tesla, both extraordinarily successful. Tesla is valued by investors as if it were a high tech company, producing a near-essential product for zero cost (i.e. a bit of software code) when in fact it creates a very tangible automobile with high cost of materials and assembly. Maybe Tesla is correctly priced as worth more than the next five or ten automobile companies combined, or maybe this is a crazy bit of madness. In any case, Musk is rich now. He is so wealthy that it was both possible and plausible for him to goof around and make an offer of $44 billion dollars to buy Twitter and take it private.

I say "goof around." Twitter's policy on blocking dangerous content had been in the news. Musk apparently agreed with some Twitter critics that their policy was unfair. He flouted the SEC rule limiting secret purchase of shares to 5% of a company by buying 9.1%. Rules? So what? He said he wanted board seats, then retracted that. He acted like a vandal to the company, not a future owner. He made what appears to be an impulsive I-can-do what-I want bid for the company. Maybe he really wanted the company, at least for that moment. Maybe it was just a big bluff. In any case, he disrupted the company and signed a contract to buy it at that price.

This is where my 30-year career as a financial advisor comes into play. A deal to buy something is a deal to buy something.

Over the course of 30 years I made recommendations to clients and received instructions to buy and sell possibly 50,000 times. When a person says, "OK, Peter, let's buy 300 shares of Microsoft," I buy 300 shares of Microsoft, right then. Maybe it goes up in price. Maybe it goes down. The client was on one side of the trade--a buyer; some nameless person was on the other side--the seller. The person who sold did so knowing that the rewards of owning Microsoft ended, and he or she had cash instead. In 30 years I had exactly five instances where a client bought or sold something, saw the market move against them in the next few days, and then said "forget it, I want to void the trade." It was a hard conversation sometimes, but I had to reaffirm that a deal is a deal, and if necessary courts would enforce it. There is a matter of honor and respect, too. There is a person on the other side of that trade. He or she relied on you.

The reality is that Elon Musk was showing off. I'm so rich I can just up and buy Twitter. It was billionaire swagger. In hindsight, if he had waited three months, he could have bought Twitter for less. He didn't wait. His offer was then, at that price. There are employees and stockholders who made life decisions based on what Musk wrote into the contract.

If Musk is such a big-shot that he can clown around about buying Twitter, then he is rich enough to pay for what he contracted to buy. Now he is saying, in effect, that he is so rich no one can make him fulfill his contract. I'm rich. No one can make me. So maybe his net worth will fall from $200 billion to $175 billion? Tough. Grow up.

If the SEC and the courts let Musk off the hook, then I will be disappointed in them, too.

Here is Levine's report:

Oh Elon |

Yesterday Twitter Inc. sued Elon Musk in Delaware to hold him to his agreement to buy Twitter for $54.20 per share. Twitter’s lawyers are hoping for a quick trial in September, so that the deal can close on schedule in October.[1] You can read Twitter’s complaint here. Here’s the gist of it:

Having mounted a public spectacle to put Twitter in play, and having proposed and then signed a seller-friendly merger agreement, Musk apparently believes that he — unlike every other party subject to Delaware contract law — is free to change his mind, trash the company, disrupt its operations, destroy stockholder value, and walk away. This repudiation follows a long list of material contractual breaches by Musk that have cast a pall over Twitter and its business. Twitter brings this action to enjoin Musk from further breaches, to compel Musk to fulfill his legal obligations, and to compel consummation of the merger upon satisfaction of the few outstanding conditions.

If you have been following the Musk/Twitter fight, here at Money Stuff or otherwise, nothing in this complaint will be a huge surprise to you. On the other hand if you have been following the Musk/Twitter fight, it is probably because you are interested in that fight, and if you are interested in that fight then Twitter’s lawsuit against Musk will probably be of interest to you. So I guess we should go through the complaint.

The basic narrative beats will be familiar. Musk secretly bought a 9.1% stake in Twitter, violating securities laws in the process, then announced that stake and agitated to join Twitter’s board:

Starting in January 2022, Musk began purchasing Twitter stock. By March 14, 2022, he had secretly accumulated a substantial position — about 5% of the company’s outstanding shares. SEC regulations required that he disclose that position no later than March 24, 2022. Musk failed to disclose, and instead kept amassing Twitter stock with the market none the wiser. By April 1, 2022, Musk had accumulated about 9.1% of the company’s outstanding shares, still in secret. ...

Meanwhile, on March 26, 2022, Musk spoke with two Twitter directors, Jack Dorsey and Egon Durban, about the future of social media and the prospect of Musk’s joining the Twitter board. Soon after, Musk told Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal and Twitter board chair Bret Taylor that he had in mind three options relative to Twitter: join its board, take the company private, or start a competitor.

So he signed an agreement to join Twitter’s board, then changed his mind and backed out of the agreement. Instead, he sent Twitter a take-it-or-leave-it unsolicited offer to buy the company for $54.20 per share in cash, and tweeted some cryptic threats to launch a tender offer if Twitter’s board didn’t sell. He also lined up committed financing from banks. So Twitter’s board negotiated a merger agreement with Musk, and they signed it on April 25.

Then the stock market went down:

The risk of market decline, which was Musk’s alone to bear under the merger agreement, materialized. Soon after signing, the U.S. capital markets took a turn for the worse. Within a week after April 25, 2022, the date the merger agreement was executed, Musk elected to sell 9.8 million Tesla shares to finance the merger at prices as low as $822.68 per share, substantially below their pre-Twitter-signing price of $1,005 per share.

So Musk tried to find some pretext to get out of the deal:

Musk wanted an escape. But the merger agreement left him little room. With no financing contingency or diligence condition, the agreement gave Musk no out absent a Company Material Adverse Effect or a material covenant breach by Twitter. Musk had to try to conjure one of those.

And because he is Elon Musk, he chose the most ridiculous imaginable pretext:

What Musk alighted upon first was a representation in Twitter’s quarterly SEC filings over many consecutive years that based on its internal processes the company estimated “the average of false or spam accounts” on its platform “represented fewer than 5% of our mDAU during the quarter.” “Monetizable Daily Active Usage or Users,” or mDAU, is a non-GAAP metric Twitter employs to measure the number of people or organizations that use the Twitter platform. …

Twitter’s SEC disclosures regarding that process and its findings are heavily qualified. As described in the “Note Regarding Key Metrics” section of its filings, Twitter’s “calculation of mDAU is not based on any standardized industry methodology,” “may differ from estimates published by third parties or from similarly-titled metrics of our competitors,” and “may not accurately reflect the actual number of people or organizations using our platform.” As for the estimate of spam or false accounts as a percentage of mDAU, Twitter explains that it is based on “an internal review of a sample of accounts,” involves “significant judgment,” “may not accurately represent the actual number of [false or spam] accounts,” and could be too low. Twitter has published the same qualified estimate — that fewer than 5% of mDAU are spam or false — for the last three years, and published similar estimates for five years preceding that.

Musk was well aware when he signed the merger agreement that spam accounted for some portion of Twitter’s mDAU, and well aware of Twitter’s qualified disclosures. Spam was one of the main reasons Musk cited, publicly and privately, for wanting to buy the company. On April 9, 2022, the day Musk said he wanted to buy Twitter rather than join its board, he texted Taylor that “purging fake users” from the platform had to be done in the context of a private company because he believed it would “make the numbers look terrible.” At a public event on April 14, Musk said eliminating spam bots would be a “top priority” for him in running Twitter. On April 21, days before the deal was inked, he declared: “If our twitter bid succeeds, we will defeat the spam bots or die trying!” Musk echoed that same sentiment in the press release announcing the merger on April 25, stating that upon acquiring Twitter he would prioritize “defeating the spam bots, and authenticating all humans.”

Yet Musk made his offer without seeking any representation from Twitter regarding its estimates of spam or false accounts. He even sweetened his offer to the Twitter board by expressly withdrawing his prior diligence condition.

On May 5, 2022, Musk announced that he had raised an additional $7.1 billion of equity commitments for the deal from 19 investors — including $1 billion from Oracle chairman Larry Ellison, $800 million from Sequoia Capital, $400 million from Andreessen Horowitz, and $375 million from a subsidiary of the Qatari sovereign wealth fund. Musk’s investors, all sophisticated market participants, made these commitments in the face of Musk’s public statements regarding spam accounts, and knowing he had forsworn diligence. Musk made his plans to address spam a key part of his pitch: As Andreessen Horowitz’s co-CEO stated in publicly announcing the investment, the firm thought Musk was “perhaps the only person in the world” who could “fix” Twitter’s alleged “difficult issue[]” with “bots.”

Musk announced that he wanted to buy Twitter because he thought there were too many spam bots. He sent in an unsolicited offer to buy Twitter, did no due diligence at all about spam bots, and asked Twitter for no representations about spam bots. He imagined that there were lots of spam bots, and he was eager to “defeat” them. And then the stock market went down, so now he is pretending that he was tricked into buying Twitter because they went around lying to him about how few spam bots there were. This pretext is bad:

Musk’s exit strategy is a model of hypocrisy. One of the chief reasons Musk cited on March 31, 2022 for wanting to buy Twitter was to rid it of the “[c]rypto spam” he viewed as a “major blight on the user experience.” Musk said he needed to take the company private because, according to him, purging spam would otherwise be commercially impractical. In his press release announcing the deal on April 25, 2022, Musk raised a clarion call to “defeat[] the spam bots.” But when the market declined and the fixed-price deal became less attractive, Musk shifted his narrative, suddenly demanding “verification” that spam was not a serious problem on Twitter’s platform, and claiming a burning need to conduct “diligence” he had expressly forsworn.

But it’s the pretext he chose, and he started tweeting about the deal being “on hold” because of the spam bot issue. He tweeted this “without any advance notice to the company.” Twitter’s executives found out the deal was on hold the same way we did, by reading Twitter, if in fact any of them read Twitter.

Twitter’s chief executive officer, Parag Agrawal, then tweeted an explanation of how Twitter estimates its bot numbers, and Musk replied with a poop emoji. You had better believe that poop emoji is in Twitter’s complaint:

If this case does not settle and ends in a landmark Delaware Chancery Court decision, that poop emoji had better be in the opinion. All the corporate law casebooks had better have that poop emoji.

In addition to being in obvious bad faith, this pretext is just completely false. In weeks of complaining about bots, Musk has never produced the tiniest sliver of evidence that Twitter’s estimates are wrong in any way:

Nor can defendants show that Twitter has made any representation or collection of representations the inaccuracy of which is “reasonably likely to result in” a Company Material Adverse Effect. They do not even try. Notwithstanding that defendants have received mountains of information regarding Twitter’s processes, far beyond what they are entitled to under the merger agreement, their termination notice asserts only that “[p]reliminary analysis by Mr. Musk’s advisors” of the vast data set Twitter provided to Musk after signing “causes Mr. Musk to strongly believe” Twitter’s reported estimates have been inaccurate. Ex. 3 at 6. Musk’s claimed “belie[f]” is of course no proof of misrepresentation, much less of a Company Material Adverse Effect — which can be established only by clearing an extraordinarily high bar that is nowhere in sight here.

Meanwhile Musk’s lawyers hit on a slightly better pretext for getting out of the deal: In the merger agreement, Twitter agreed to provide information to Musk that he reasonably requests “for any reasonable business purpose related to the consummation of the” merger. So Musk’s team just sent in more and more ridiculous requests for information about spam bots:

On May 21, 2022, Twitter hosted a third diligence session with Musk’s team and yet again discussed Twitter’s processes for calculating mDAU and estimates of spam or false accounts. Twitter also provided a detailed summary document describing the process the company uses to estimate spam as a percentage of mDAU.

Defendants responded with increasingly invasive and unreasonable requests. And rather than use “reasonable best efforts to minimize any disruption to the respective business of the Company and its Subsidiaries that may result from requests for access,” Ex. 1 § 6.4, defendants repeatedly demanded immediate responses to their access requests. The scope of the requests and the deadlines defendants imposed on their satisfaction were unreasonable, disruptive to the business, and far outside the bounds of Section 6.4.

Twitter nonetheless continued to work with Musk to try to respond to the requests. It extended an ongoing offer to engage with Musk and his representatives regarding its calculation of mDAU, and held several more diligence sessions through the end of May. It also provided detailed written responses, including custom reporting, to his escalating requests for information. …

The June 17 letter further contained a litigation-style discovery demand for information Musk asserted was needed to investigate “the truthfulness of Twitter’s representations to date regarding its active user base, and the veracity of its methodologies for determining that user base.” It broadly demanded board materials relating to mDAU and spam, as well as emails, text messages, and other communications about those topics — highly unusual requests in the context of good faith efforts toward completion of any merger transaction, and absurd in the context of this one, which has no diligence condition. Musk propounded these unreasonable requests and touted his contrived narrative about Twitter’s methodologies, all without ever identifying a basis for questioning the veracity of Twitter’s methodologies or the accuracy of its SEC disclosures.

The purpose of these requests was certainly not to work toward closing of the merger, which was the only reason that Musk was allowed to demand information. It wasn’t even really to understand how many spam bots Twitter has. The purpose of these requests was to be so unreasonable — to ask for so much information, and for sensitive competitive and user information that Twitter couldn’t give Musk[2] — that Twitter would say no, and then Musk could say “aha, you didn’t give me the information I asked for, I can walk away.” You can tell because Musk ignored the information that Twitter did give him:

Agrawal and Twitter CFO Ned Segal had been trying to set up a meeting with Musk to discuss the company’s process in estimating the prevalence of spam or false accounts. On June 17, 2022, Segal proposed a discussion with Musk and his team to “cover spam as a % of DAU.” Musk responded that he had a conflict at the proposed time. When Agrawal sought to reengage on the matter, Musk agreed to a time on June 21, but then bowed out and asked Agrawal and Segal to speak with his team not about the spam estimation process but “the pro forma financials for the debt.” …

Musk exhibited little interest in understanding Twitter’s process for estimating spam accounts that went into the company’s disclosures. Indeed, in a June 30 conversation with Segal, Musk acknowledged he had not read the detailed summary of Twitter’s sampling process provided back in May. Once again, Segal offered to spend time with Musk and review the detailed summary of Twitter’s sampling process as the Twitter team had done with Musk’s advisors. That meeting never occurred despite multiple attempts by Twitter.

Musk simply doesn’t care how many spam bots Twitter has, or how it estimates that number; he just wants to get out of the deal, and endlessly asking for more information is a way to manufacture an excuse to get out of the deal. Twitter argues that that can’t possibly work:

Twitter has provided defendants far more information than they are entitled to under the merger agreement. Section 6.4 serves the narrow purpose of giving Parent reasonable access to information necessary to close the merger. It does not give defendants a broad right to conduct post-signing due diligence of a kind they specifically forswore pre-signing. Much less does it give Musk the right to hunt for evidence supporting a bogus misrepresentation theory developed to try to torpedo the deal.

Musk has one more pretext for terminating the deal, which is that Twitter supposedly did not ask him for permission to fire a couple of senior employees and freeze hiring. One problem with this pretext is that it’s not true:

While erring on the side of seeking consent, Twitter has continued to operate in the ordinary course respecting routine management decisions, including decisions concerning termination and hiring of individual employees. In early May, Twitter let go of two executives and announced it would be “pausing most hiring and backfills” as positions became vacant. Musk’s counsel was notified of those decisions at the time and raised no objection.

Another problem is that the contract allowed Twitter to fire people without Musk’s consent[3]:

Twitter specifically negotiated for the right to terminate employees, including executives, without first having to obtain Musk’s consent. Musk had notice back in early May of many of the actions about which he now complains for the first time. He did not object then or at any point prior to his purported termination notice on July 8, because there was no violation.

A third problem is that it’s what Musk wanted:

These decisions aligned with Musk’s own stated priorities. Days after signing, on April 28, 2022, Musk texted Twitter’s board chair to say his “biggest concern is headcount and expense growth.” In a meeting with Twitter management on May 6, 2022, Musk again asserted that the company’s headcount was high and encouraged management to consider ways to cut costs. Musk repeated these themes in conversations with Agrawal and Segal throughout May and June. On June 16, Musk held a virtual meeting with Twitter employees. Asked what he was “thinking about layoffs at Twitter,” Musk responded that “costs exceed the revenue,” “so there would have to be some rationalization of headcount and expenses.” In his final conversation with Segal before purporting to terminate, Musk expressed his concern about Twitter’s expenses and asked why Twitter was not considering more aggressive cost cutting. And, as noted, Musk has refused to approve — or even discuss — Twitter’s proposed retention programs for key employees.

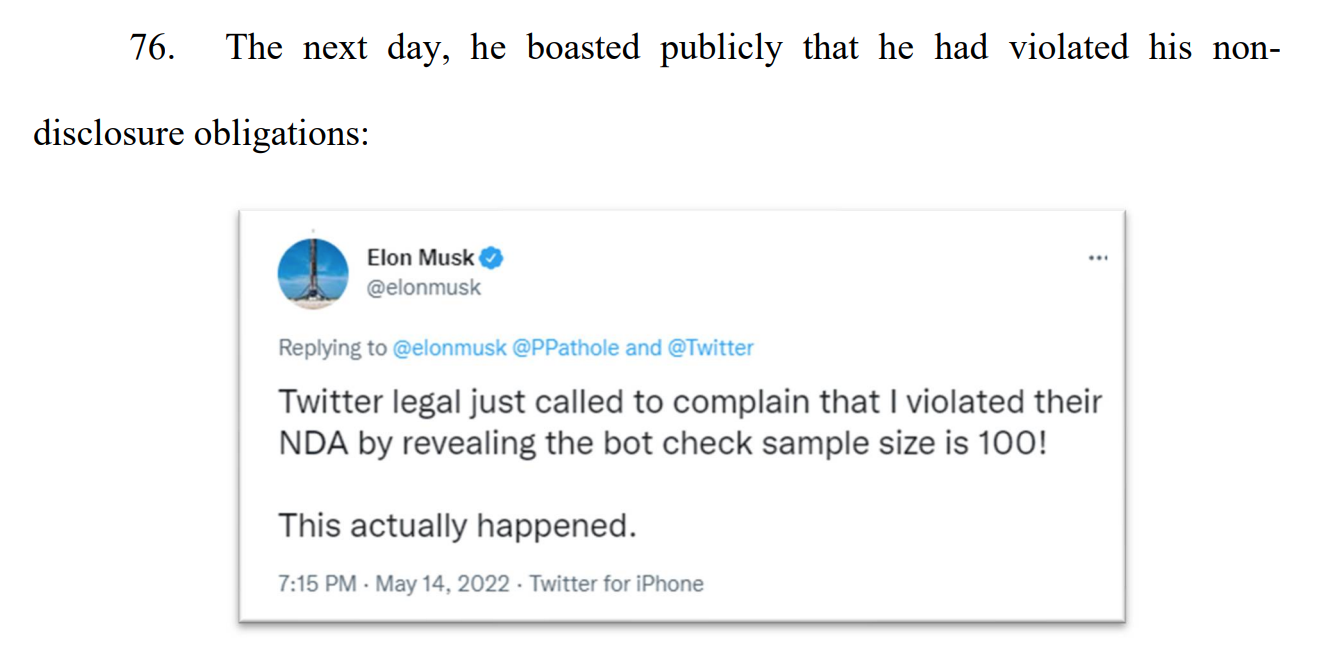

Twitter’s lawyers also point out that Musk himself constantly violates his obligations under the merger agreement. The merger agreement says that Musk can tweet about the deal, “so long as such Tweets do not disparage the Company or any of its Representatives,” but of course “since signing the merger agreement, Musk has repeatedly disparaged Twitter and the deal, creating business risk for Twitter and downward pressure on its share price.” After a due diligence meeting in May where Twitter “explained, among other things, that its spam estimation process entails daily sampling for a total set of approximately 9,000 accounts per quarter that are manually reviewed,” “Musk Tweeted publicly a misrepresentation that Twitter’s sample size for spam estimates was just 100.”[4] And then:

The narrow point of this argument is that “the merger agreement provides that if defendants are in material breach of their own obligations under the merger agreement, they cannot exercise any termination right they might otherwise have.” (See section 8.1(d).) So when Musk sent a letter terminating the merger agreement, it didn’t work, because he was breaching his own agreements right and left. So the agreement is un-terminated and he has to keep working to close the deal.

But there is also a broader point to this argument. Ultimately what Twitter wants here is a judgment of specific performance, “ordering defendants to specifically perform their obligations under the merger agreement and consummate the closing in accordance with the terms of the merger agreement.” The merger agreement says Twitter can get that judgment, but it’s not up to the merger agreement, it’s up to the judge. And it is a somewhat drastic remedy, forcing an unwilling buyer to pay $44 billion for a company that he doesn’t want. It is an “equitable” remedy, and a court will not order it unless “the balance of equities tips in favor of the party seeking performance.” If it feels unfair to a judge to order Musk to close, she’s not going to order him to close.

The fact that Musk has been acting in transparently bad faith all along — that he started this process by violating SEC disclosure rules, that he agreed to join Twitter’s board and then backed out of that agreement, that “bots” were the reason he wanted to buy Twitter before they became his excuse for getting out of the deal, that he has disparaged Twitter and its executives from the time he signed the deal, that he violated his nondisclosure obligations and then boasted about it on Twitter — these things are not all relevant as a legal matter (some of them are), but they are as an equitable matter. They make it clear that Musk does not care about contracts, that he ignores the law, that he will not live up to his word. The point is to make the judge angry at him, so that she will make him do what he promised to do.

I joked above about this case turning into a landmark Delaware Chancery Court decision, but honestly I don’t see it? We have not yet seen Musk’s reply, and perhaps I am missing something, but so far this case seems very simple to me. We talked yesterday about the DecoPac Holdings Inc. case, decided last year by Delaware Chancellor Kathaleen McCormick. A private equity buyer agreed to buy a company, the market went down, the buyer manufactured pretexts to get out of the deal and blow up its financing, and the target sued for specific performance. The buyer’s pretexts there were not as laughable as Musk’s here, and the buyer there did not go around tweeting about how gleefully it was violating the terms of the merger agreement, but the judge ordered it to close anyway. “This court has not hesitated to order specific performance in cases of this nature,” she wrote, and she didn’t.

But that case was a private equity firm buying a cake-decorating company from another private equity firm. The seller was economically motivated, and the buyer was economically motivated, and the market went down and they fought over who had to eat the loss. The buyer lost and had to close the deal, so now it owns the cake-decorating company. And presumably it will run it as well as it can, so that it can make as much money as possible decorating cakes. The buyer, a private equity firm, is not mad at the cakes; it is not going to smash them all out of pique. It’s just business.

This case is a little different. Musk did want to buy Twitter for some reason? I think?[5] It is possible that his reason was to make a lot of money, but he specifically disclaimed that, and his plans to make a lot of money seemed pretty half-baked. Instead his reasons for wanting to own Twitter were like … pique? Politics? Free speech? Getting more publicity for himself? Making the experience of using Twitter more pleasant for him personally? Fighting bots? Adding an edit button? Diversifying his meme-lord portfolio? Improving the fate of humanity?

Meanwhile Twitter’s board quickly agreed to sell because it wanted the money for shareholders. Back in the simpler times of earlier May, I was critical of this decision. I wrote:

A lot of people think of Twitter as a public utility, a public trust, “the town square,” a company with an important social mission that many of its users and employees and Elon Musk care about deeply. And its CEO and board of directors essentially can’t bring themselves to talk about it. When employees asked him about what was best for the company, Agrawal could talk only about the shareholders. Elon Musk is not at all embarrassed to say that Twitter has an important public mission, which is why he’s buying it. But its current management can’t say that, which is why they’re selling it.

I want to be clear here that I am not saying that it was a bad decision, for Twitter’s product or users, to sell to Elon Musk. I have no idea; that’s not the point. The point is that the board seems to have put almost no weight on these questions. (Except Jack Dorsey, who does seem to have thought that Musk would run Twitter better than he did, and who seems happy about the sale.) I have written this before, but the basic problem with Twitter’s management and board of directors seems to be that they do not care about Twitter, as a company or as a product, so they are left to care about shareholders. This seems bad for everyone, including shareholders.

Well but it’s worse now isn’t it? Back in May, at least some people thought that Elon Musk would be good for Twitter as a product, a company, a town square. Now he is on a very public mission to destroy Twitter, get rid of employees, drive away advertisers and spark regulatory investigations. He wants to “trash the company” and “disrupt its operations,” as Twitter’s own lawyers say, as they demand that he buy the company. Seems like a bad guy to own the company!

As a matter of shareholder value, Twitter’s efforts here are unassailable: If Musk is hellbent on destroying Twitter, he should really pay its current shareholders $54.20 per share in cash first. But if you think of Twitter as something other than a pot of cash for shareholders — if you care about its employees or its users or its public mission — then the last thing you would want would be for this guy to own it.

One can sympathize with Twitter co-founder Ev Williams. “I’m sure there are legal/fiduciary reasons” that the board has to push Musk to close, he tweeted. “But if I was still on the board, I’d be asking if we can just let this whole ugly episode blow over. Hopefully that’s the plan and this is ceremony.” I mean, no: The shareholders definitely want their $54.20 rather than nothing, and the board really does have to try hard to get it for them. Also it is bad to let Musk go around destroying public companies on a whim without any consequences; Twitter’s board has sort of a public-service obligation to try to make him pay. Still, Williams has a point. He co-founded Twitter, presumably he likes Twitter, and now Elon Musk is trying to destroy it, and Twitter’s board is trying to force him to follow through. What is the good outcome here?

You could imagine a fantasy solution. A judge orders Musk to close on the deal but put Twitter in a public trust where he can’t meddle with it (or tweet). A judge says “never mind the damages cap in the merger agreement, I’m awarding $40 billion of punitive damages.” Other dumb stuff. We talked on Monday about the realistic outcomes: The judge will let Musk off the hook for $1 billion (or less), or the judge will order him to close the deal and buy Twitter, or Musk and Twitter will settle for him buying Twitter at a lower price, or they’ll settle for him walking away at a higher price. The last of these seems the best to me — Twitter’s shareholders are compensated, Musk is held to his word, he doesn’t actually own Twitter — but it requires Musk to agree to settle. And to get him to settle, I do think Twitter needs to convince him that they will otherwise get specific performance and make him close the deal. Nobody wants that, I don’t think (I hope!), but they have to fight for it anyway.

If you'd like to get Money Stuff in handy email form, right in your inbox, please subscribe at this link. Or you can subscribe to Money Stuff and other great Bloomberg newsletters here. Thanks!

[1] Disclosure: Twitter’s lawyers include Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. I worked there, uh, 15 years ago now. I suppose this creates an appearance of bias, but in my defense I have taken a pretty consistent line on the Musk/Twitter deal for months now, and they hired Wachtell on Friday.

[2] In particular, the merger agreement says that Twitter does not have to give Musk any information that would, in its “reasonable judgment,” “cause significant competitive harm to the Company or its Subsidiaries if the transactions contemplated by this Agreement are not consummated.” As Twitter’s lawyers point out: ”On May 27, 2022, Twitter responded by noting its weeks-long active engagement with Musk’s team and explaining that some of defendants’ requests sought disclosure of highly sensitive information and data that would be difficult to furnish and would expose Twitter to competitive harm if shared. After all, Musk had said he would do one of three things with Twitter: sit on its board, buy it, or build a competitor. He had already accepted and then rejected the first option, and was plotting a pretextual escape from the second. Musk’s third option — building a competitor to Twitter — remained.” It will be pretty insane if Musk gets out of his deal to buy Twitter and then builds a Twitter competitor.

[3] Technically what happened here is that the original draft of the merger agreement that Musk’s lawyers sent to Twitter “would have deemed the hiring and firing of an employee at the level of vice president or above a presumptive violation of the ordinary course covenant absent Musk’s consent,” Twitter’s lawyers crossed that out, and Musk agreed to the revised version. This is not *definitive proof* that Twitter was allowed to fire senior employees without his consent — Musk can still argue that firing these employees was not “in the ordinary course of business” — but it is helpful for Twitter that it was specifically negotiated.

[4] Hmm. A “misrepresentation”? A quarter is like 90 days, so daily sampling for 9,000 accounts per quarter would seem to be about 100 accounts per day. I can see his point here. Their point, though, is that he’s not supposed to disclose what they tell him publicly, and he’s especially not supposed to brag about breaching his confidentiality agreement.

[5] Maybe his plan all along was to pretend to buy Twitter, ruin its business and run away? That seems pretty far-fetched, but on the other hand Musk keeps tweeting memes suggesting that it’s true? That this was all a galaxy-brain plan to expose Twitter’s bot problem? Okay.

6 comments:

Tesla looks less inviting with all this. Do people really want to support someone like him? I think he is ruining his own marketing brand, but doesn’t realize or care. I predict Tesla stock going lower as a result. Owning Tesla is less a showpiece than it was.

I could just not comment, but I will.

We need cheap electric cars, not electric Rolls Royces, and we certainly don't need a company that spends billions to send William Shatner into space for 12 minutes.

Twitter and Mush deserve each other.

The rest of us deserve better.

Elon Musk’s net worth is over $200 billion – more than the GDP of most countries and over one and a half million times the median net worth in the U.S. It would be absurd to tolerate such out-of-control wealth disparity and still expect the super-rich to feel bound by the same standards of conduct that govern the rest of us.

Musk created SpaceX, the world’s best rocket company, the innovator of reusable launchers that drastically reduced the cost of getting into space.

That’s worth forgiving all of his shenanigans, in my book.

Much has been written over the years about neuroscience and the connection between socioeconomic status and well-being, but recent studies have been finding strong correlations with how wealth and power may biologically change the brain. The recent Atlantic article talks about Michael Flynn’s dramatic personality change – from a lifetime of solid “by the book” kind of public/military servant, who converted to not just a Trump sycophant, but a true believer, a complete shift in worldviews about what is good and right and just.

Looking throughout history, it seems it is the rare individual who achieves a high level of wealth or power, who does not seem to go at least little insane. Just Google “wealth”, “power” and “neuroscience” and you’ll get dozens of reputable articles like this one in The Psychologist, or this paper published in the NIH journal, and The Business Insider.

If we are honest, who among us has not experienced at least some kind of "empathy deficit" when we’ve been in positions of even a little power? I remember with some embarrassment, having a few jobs with fancy-pants titles and big firms with lots of perks, getting my "ego fix" invited to keynote large international conferences and serving on prestigious boards. Reflecting back now I think “what a crock” and remember I might have been a complete ass to some people -especially those closest me. This is especially humbling because I also had this so-called “reputation” of serving charitable causes.

So Musk and Bezos and their ilk are likely playing out some pathological combination of nature and nurture, but perhaps their behaviors (along with Trump) are amplified by some kind of neurobiological phenomenon that afflicts all of us.

Chimpanzees when elevated into the dominant position have their serotonin levels increase. Take that chimpanzee and put him in another setting where he is not dominant and his serotonin level drops. Yes, when people get put in positions of power their serotonin levels increase.

Post a Comment